In London, the night has always had a rhythm of its own - from the clink of tankards in 18th-century gin dens to the thump of bass in East London warehouses. This city never sleeps, but it has changed how it stays awake. The story of London nightlife isn’t just about music or drinks; it’s about survival, rebellion, class, and identity stitched into alleyways, backrooms, and basement clubs that still echo with the ghosts of past generations.

The Gin Craze and the Birth of London’s Night Culture

In the early 1700s, London’s streets lit up not by neon, but by gin. The Gin Act of 1736 tried to curb the madness - over a million gallons consumed annually, mostly by the poor - but it only drove the trade underground. Gin palaces, with their ornate mirrors and gaslit interiors, became the first real nightlife venues. Places like the famous Old Curiosity Shop in Lambeth weren’t just bars; they were social hubs where laborers, prostitutes, and petty thieves mingled under one roof. The smell of cheap gin, sweat, and coal smoke clung to the walls. By 1750, there were more than 15,000 gin shops in London. It wasn’t entertainment - it was escape.

Pubs, Music Halls, and the Rise of the Working-Class Night

By the Victorian era, pubs had evolved into something more respectable, though no less essential. The Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese on Fleet Street, still standing today, hosted writers like Charles Dickens and Mark Twain. These weren’t tourist spots then - they were where dockworkers, clerks, and street vendors ended their days. The pub wasn’t just a place to drink; it was a community center, a voting booth, and sometimes, a courtroom.

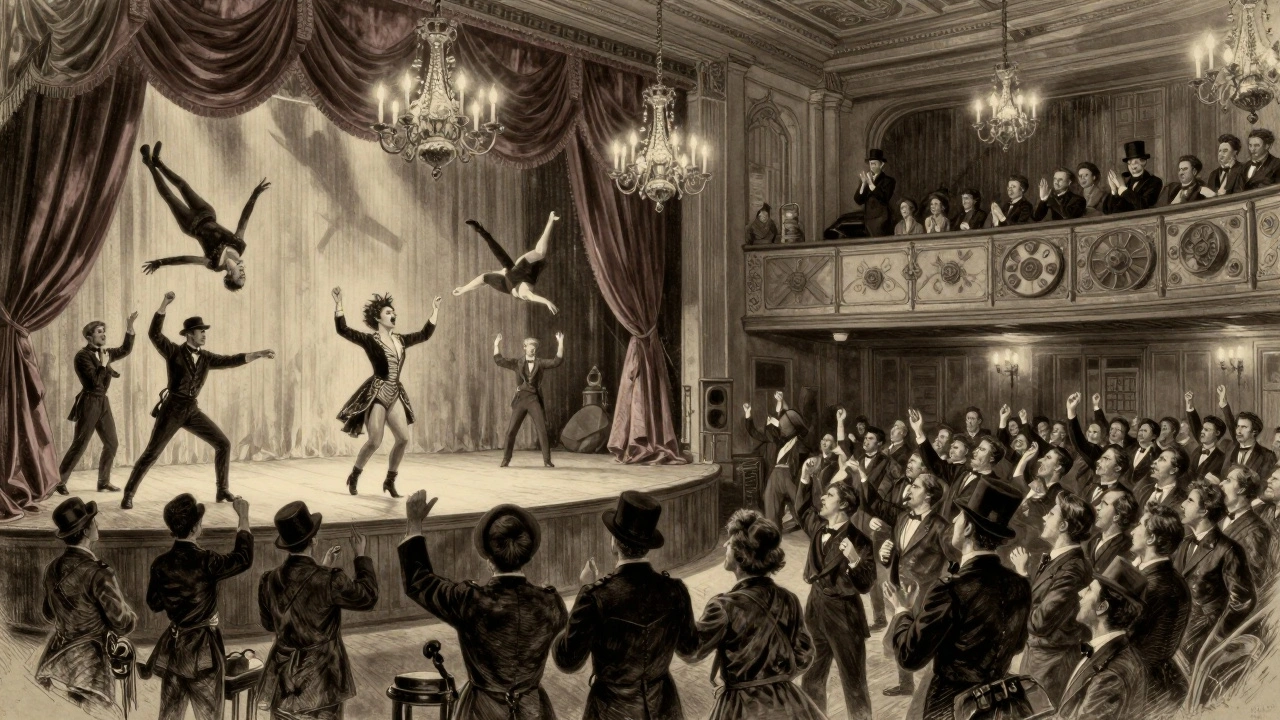

Music halls emerged in the mid-1800s as the first true performance venues for the masses. The London Pavilion on Piccadilly and the Hoxton Hall in Hackney drew crowds with comic songs, acrobats, and drag acts. These shows were raucous, irreverent, and often banned by moral reformers. The audience? Factory workers, soldiers on leave, and women who had no other public space to gather after dark. The music hall was democracy in action - and it was loud.

The Jazz Age and the Birth of Soho

After World War I, London’s nightlife began to shift south. Soho, once a red-light district with a reputation for vice, became the heartbeat of the city’s after-hours scene. The 1920s and 30s brought jazz, speakeasies, and a new kind of glamour. The Flamingo Club on Wardour Street, opened in 1952, was where British mods, Caribbean immigrants, and American GIs danced to ska and R&B. It was one of the first integrated clubs in London - a radical idea in a still-segregated society.

By the 1960s, Soho was the place to be. The Bag O’Nails on Kingly Street hosted early gigs by Jimi Hendrix and The Rolling Stones. The Blues Club on Dean Street became a pilgrimage site for blues lovers. These weren’t just venues - they were incubators. London’s youth culture was being forged in the smoke and sweat of these cramped rooms, where race, class, and music blurred into something new.

The Acid House Revolution and the Warehouse Scene

By the late 1980s, London’s nightlife had fractured. The punk and post-punk scenes had burned out, and the city felt tired. Then came acid house. In 1988, a wave of illegal raves exploded across abandoned warehouses in East London - places like the Old Truman Brewery and the St. Katharine Docks. These weren’t clubs; they were temporary utopias. Thousands of teenagers, students, and factory workers would take the Tube to the edge of the city, climb through broken fences, and dance until dawn to Roland TB-303 basslines.

The government responded with the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, which targeted gatherings with “repetitive beats.” But the damage was done. The rave culture had changed London forever. It wasn’t just about drugs or music - it was about reclaiming space. The same warehouses that once held coal and cargo now hosted the future.

Modern London: From Soho to Dalston and Beyond

Today, London’s nightlife is a patchwork of micro-scenes. Soho still has its bars - The French House on Dean Street, where the same stools have held writers, musicians, and drag queens since the 1950s - but the center of gravity has shifted. Dalston, in Hackney, is now the place for queer nights, underground techno, and experimental sound systems. The Knockdown Center-style venues like Rich Mix and Mojo Club host everything from Afrobeat to noise pop.

Shoreditch’s The Box and Printworks (now closed but still a legend) turned former printing factories into immersive club experiences with laser shows, live performers, and DJs who traveled from Berlin and Detroit. Meanwhile, in Peckham, Waves and The Bull’s Head blend jazz, reggae, and house in a way only South London can.

Even the traditional pub isn’t dead. The Red Lion in Camden still serves real ale and hosts open-mic nights. The Wheatsheaf in Fitzrovia, once a haunt of George Orwell, now has craft cocktails and vinyl spinners on weekends. London’s pubs have adapted - they’re not relics. They’re living rooms with beer taps.

What Keeps London’s Night Alive?

What makes London’s nightlife different from Paris, New York, or Berlin? It’s the chaos. There’s no single scene. There’s no one rule. You can go from a 17th-century gin palace in Covent Garden to a 3 a.m. trap party in Croydon - and both feel equally London.

The city’s nightlife survives because it’s messy, inclusive, and stubborn. It’s run by people who don’t have money but have passion. It’s sustained by immigrants who brought their rhythms - from Nigerian highlife to Turkish pop to Polish techno. It’s kept alive by landlords who turn empty shops into pop-up clubs, by DJs who play for free, and by students who walk 10 miles after last train to find one more song.

London’s nightlife isn’t about luxury. It’s about belonging. And that’s why, even as rent rises and licensing laws tighten, it never dies. It just moves. To a new basement. To a warehouse in Brixton. To a rooftop in Walthamstow. To a pub that doesn’t even have a name yet.

Where to Experience London’s Nightlife Today

- For history: Visit the Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese or The French House - both still serve drinks the same way they did 100 years ago.

- For underground beats: Head to Rich Mix in Shoreditch or Waves in Peckham - no VIP lists, no cover charge before midnight.

- For queer nights: Try Stonewall in Soho or Club Kali in Dalston - the oldest and newest queer spaces in the city.

- For late-night eats: Grab a kebab from Wahaca or a bagel from Beigel Bake on Brick Lane - the only thing that’s stayed open since the 1970s.

- For secret spots: Follow @london.nightlife on Instagram - it’s run by locals who post pop-up events 24 hours before they happen.

London’s night doesn’t need a brochure. It doesn’t need to be marketed. It just needs you to show up - with an open mind, a good pair of shoes, and maybe a spare £5 for the bus home.

What’s the oldest pub in London still serving drinks?

The Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese on Fleet Street has been serving patrons since 1667, though the current building dates to 1766 after a fire. It still has original oak beams, gas lamps, and a cellar that once held smuggled brandy. You can still sit where Dickens wrote and where Samuel Pepys drank.

Why did London’s music halls disappear?

Music halls declined after World War II because of television, rising rents, and changing tastes. Many were demolished or turned into cinemas. But their spirit lives on in comedy clubs like The Comedy Store in Soho and in the chaotic energy of modern drag shows at Stonewall or Club Kali.

Are there still illegal raves in London?

Officially, no - but underground parties still happen. The police now focus on safety, not shutting down events. Many are held in disused buildings, shipping containers, or even on barges along the Thames. They’re advertised through word-of-mouth, encrypted apps, or local flyers. If you’re looking for one, follow local DJs on Instagram or check out London Nightlife on Telegram.

How has gentrification affected London nightlife?

Gentrification has pushed out many grassroots venues. Clubs like The Fridge in Brixton and The Wag Club in Camden are gone. But new spaces keep rising - often in less expensive areas like Croydon, Lewisham, and Romford. The key is that these new spots are community-run, not corporate-owned. The spirit of rebellion hasn’t left; it’s just moved.

What’s the best way to experience authentic London nightlife as a visitor?

Don’t go to the tourist traps. Skip the clubs on Oxford Street. Instead, take the Night Bus to a local pub in Southwark or Hackney. Talk to the bartender - they’ll tell you where the real music is playing. Or go to a Sunday jazz session at The Bull’s Head in Barnes. Authentic London nightlife isn’t about fame - it’s about finding the place where the locals feel at home.

Final Thoughts: London Never Closes - It Just Changes

London’s nightlife has survived plagues, wars, puritans, and property developers. It’s been policed, censored, and commercialized. But every time it’s been pushed down, it’s come back louder. That’s the truth of this city: its night belongs to the people who show up, not the ones who own the doors.

If you want to understand London, don’t visit the Tower or the London Eye. Go out after midnight. Find a pub where the walls are stained with decades of smoke. Listen to the laughter from a backroom where someone’s telling a story only a Londoner would get. Dance until your feet ache in a basement where the music doesn’t come from a playlist, but from a soul.

That’s when you’ll know - London’s night isn’t just alive. It’s still writing its next chapter.